Systems designed to protect space tend to prioritise defending certain areas of the pitch aggressively, while allowing the opponent possession in others. Those seeking to protect possession are more likely to embrace a player-to-player (P2P) system in an effort to win the ball back as quickly as possible, likely exposing spaces behind their press which are vulnerable.

That’s not to say that each pressing style fits into one, tidy category. Space vs possession should be viewed as a spectrum: to protect one, you have to embrace a trade-off of the other.

Of course, both scenarios also have other benefits. By going P2P and limiting the opponent’s time in possession, they also protect space by preventing the ball from being played forward. Similarly, in a zonal system, there may be areas of the pitch where the opponent would be pressed aggressively if they entered it – thus protecting possession in these areas.

This concept has become more nuanced in recent years. In Pep Guardiola’s first season at Manchester City, he was clear to his players that “the ball is ours, and when they’ve got our ball, we have to get it back” (sourced from ‘The Pep Revolution’). Fast forward almost a decade, and City had just 33% possession against Arsenal a few weeks ago. Why? Because they chose to lean towards protecting space.

The beautiful truth of modern pressing systems is that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution, which is why each manager will make adaptations to suit their team’s strengths or coaching principles. Having said that, each pressing style is based on one of the following ideas.

High Press

A high press is the furthest system on the ‘protect possession’ end of the spectrum. At its core, the aim of a high press is to limit the opponent’s time on the ball regardless of the area of the pitch they may have it, with the aim of regaining possession quickly.

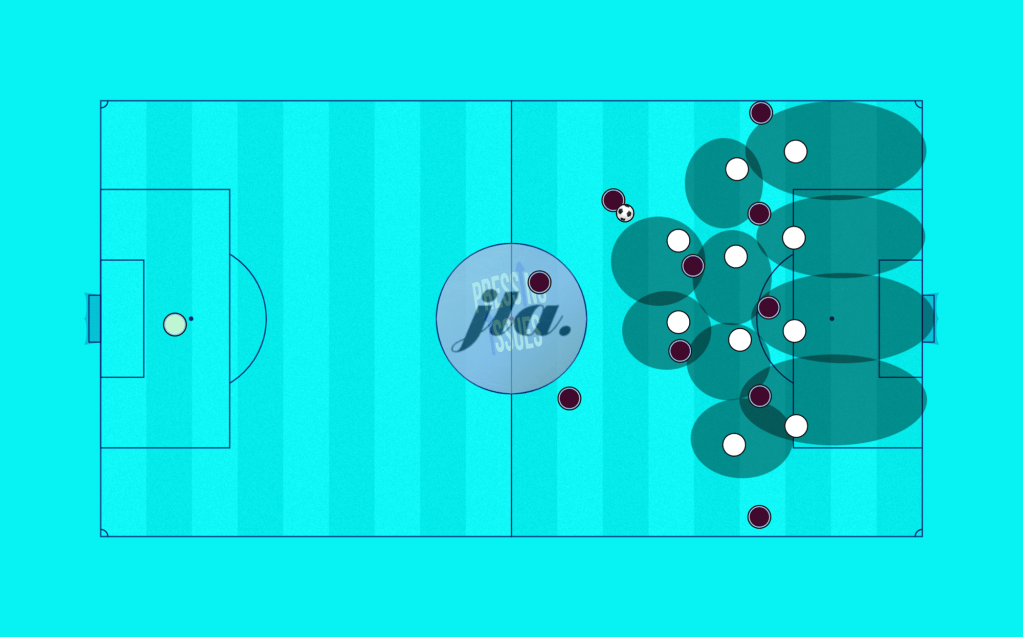

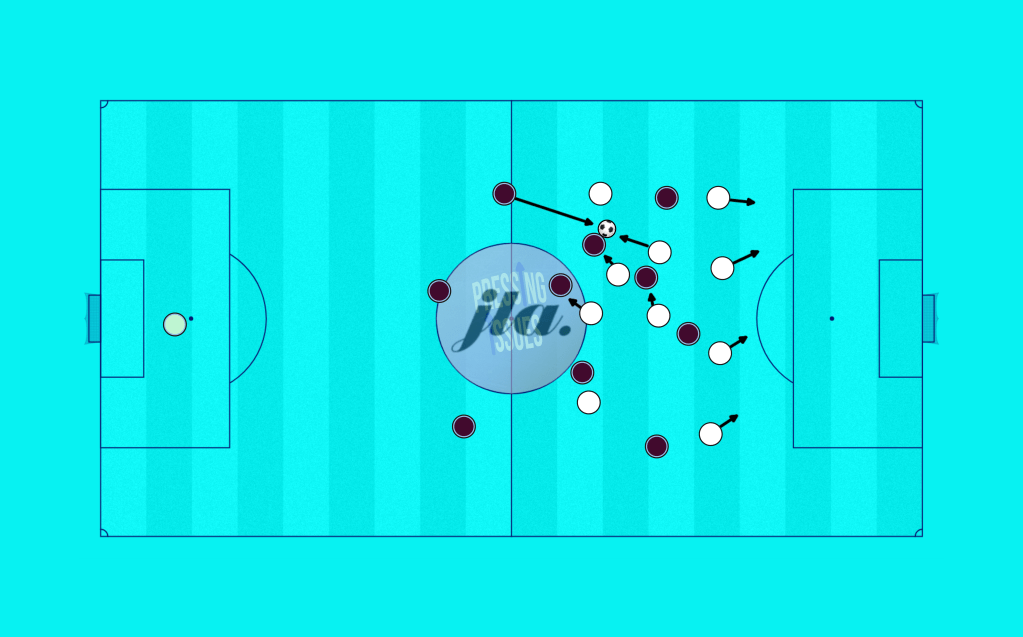

As seen above, a high press is usually a P2P system which limits space and passing options for the team in possession. It achieves this by pushing multiple players forwards, with each defensive player ‘attaching’ themselves to someone in order to prevent ball progression.

This pressing style, when done effectively, can make the team in possession feel strangled. It forces them to either play high-risk passes to attempt to play through the press and potentially exploit the space left behind the OOP team, or, as is more often the case, play the ball long and forwards, where the OOP team have a 4-3 advantage (owing to most teams keeping their centre-backs doubled up on the opponent’s striker).

That isn’t always the case, though. At its most extreme, usually in situations where the OOP team is losing and needs to recover possession quickly, they may commit to an entirely P2P system. But that’s incredibly high risk.

As such, most teams will initiate a high press only under certain conditions. These are often called ‘pressing triggers’, and include (but aren’t limited to): pressing when a certain player is in possession, when the ball goes into a certain area of the pitch or when the opposing team play a backwards pass.

The highly P2P and aggressive style of a high press means that it’s very rare for a team to use it throughout a whole game. It is far more likely to be used in short bursts and key moments, such as the start of the game, or towards the end if a team is losing. However, elements of a high press will be discussed when investigating ‘hybrid pressing’ later on.

Mid-Press (or midblock)

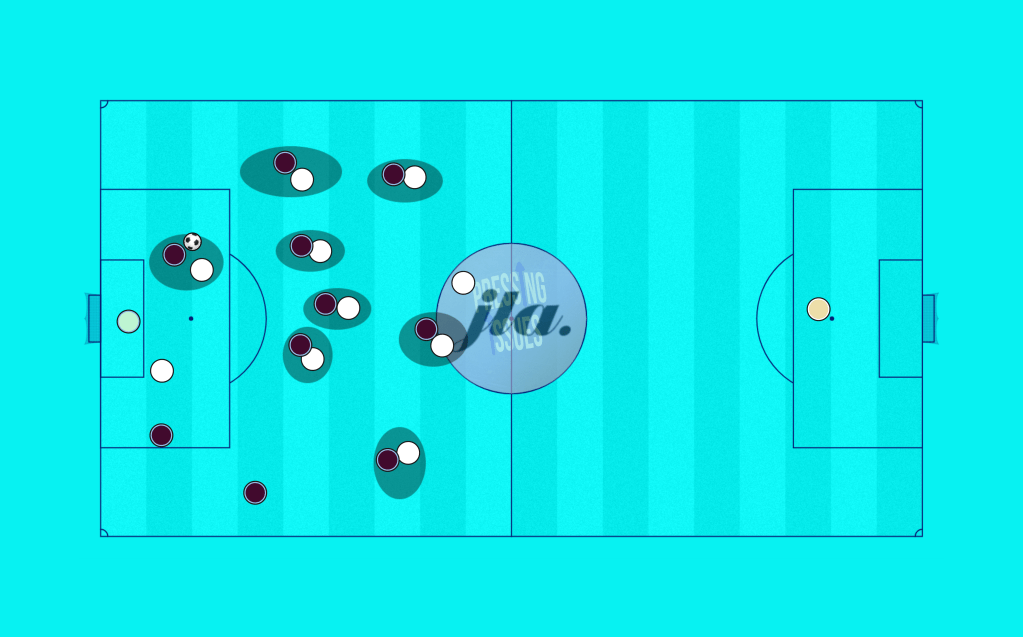

As the name suggests, a midblock is less aggressive than a high press. Where a high press is very energy consuming and can be high risk, a midblock is generally considered a nice middle ground between protecting possession, but also keeping control of key areas of the pitch.

A midblock has become a common approach for both mid-table and elite Premier League sides owing to its balance and versatility. It allows teams to defend with a solid structure, while also being able to press aggressively in the right moments.

The midblock’s popularity stems from its balance, but it, like every pressing system, isn’t perfect. When teams are patient in their build-up and strategic in pulling certain players out of position, big gaps between the midfield and defensive lines can open up and be exploited.

Low Block

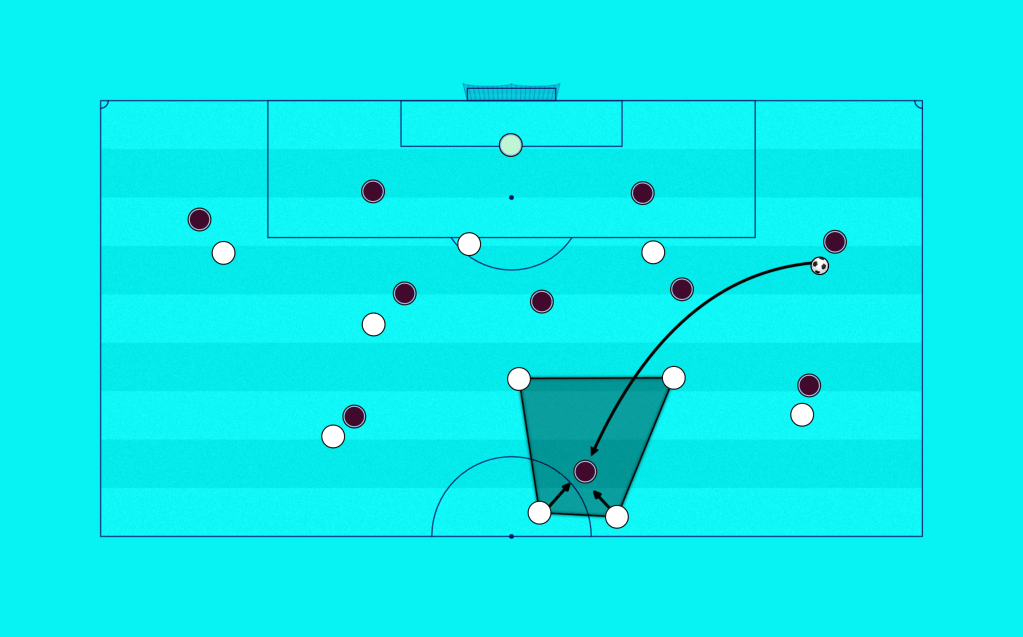

The third and final primary principle of pressing is a low block, which, put simply, is the most space-protective style of pressing on this list. It prioritises defending the most threatening areas of the pitch, with each player being responsible for a ‘zone’.

The low block is typically associated with teams who are technically inferior to their opponents, as it provides the most protection over the areas of the pitch from which a team is most likely to score. It’s also not completely rigid: plenty of low blocks can involve two players ‘doubling up’ on an opponent player, if the opposing team has a particularly dangerous winger, for example.

Hybrid Pressing

Hybrid pressing was a term coined by football analyst Jon Mackenzie in 2023, and his pieces exploring the system’s evolution in detail is well worth a read. Put simply, however, hybrid pressing is a style by which teams look to enjoy the benefits of each pressing style, by switching between them depending on different phases of the opponent’s build-up. It looks to protect possession in the moments where it is prudent while also being able to protect space if it is necessary.

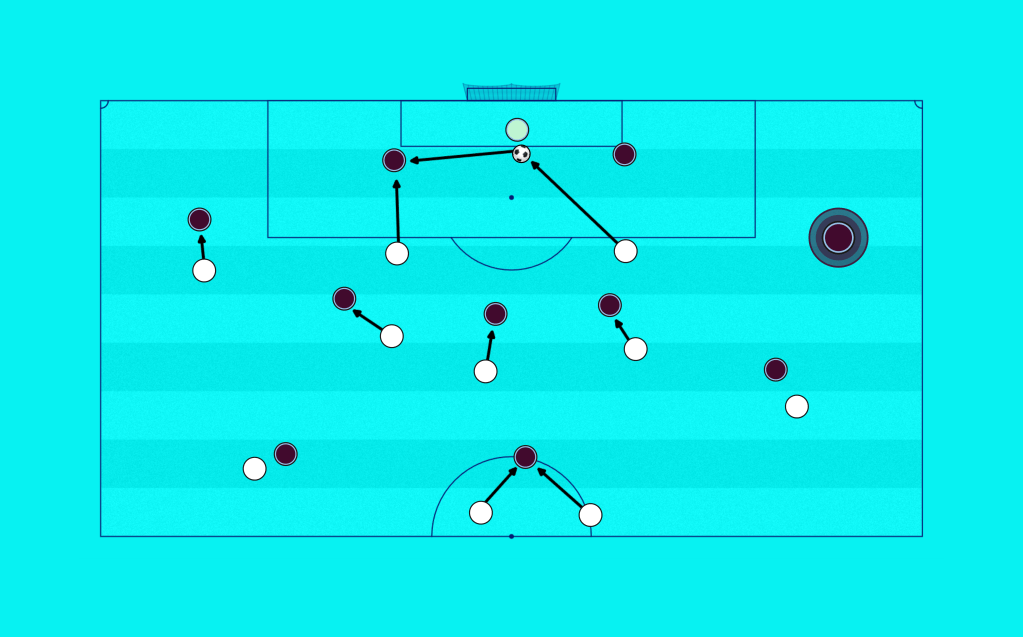

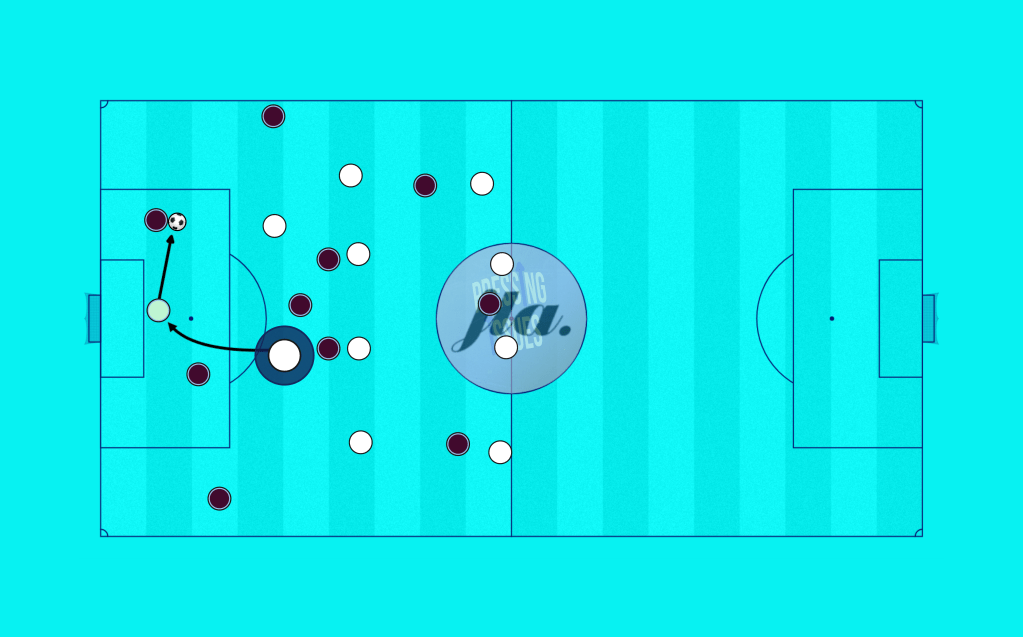

In the high press phase, many teams will look to essentially cut the pitch in half: going P2P on one side of the pitch to limit the ball carrier’s options.

The player highlighted above is what MacKenzie dubbed ‘the hybrid player’, whose role changes depending on which side of the pitch the ball goes to. It is usually a winger who engages in this role, and how effective the hybrid player is in their role will dictate whether the OOP stay in their high press phase, or shift into a midblock.

Where the hybrid press differs to a high press is that many teams have become content to abandon the idea of double coverage of the opponent’s striker, in favour of being able to transition more smoothly from one phase to the next.

The hybrid player’s role is essentially to jump to whichever player is nearer the ball. Say, like in the image above the ball goes out to the left, the winger will jump onto the opponent’s right centre-back to cover the short pass. If the ball goes to the right, they will immediately press the right-back and the whole team will shift over, with the right winger then becoming the hybrid player.

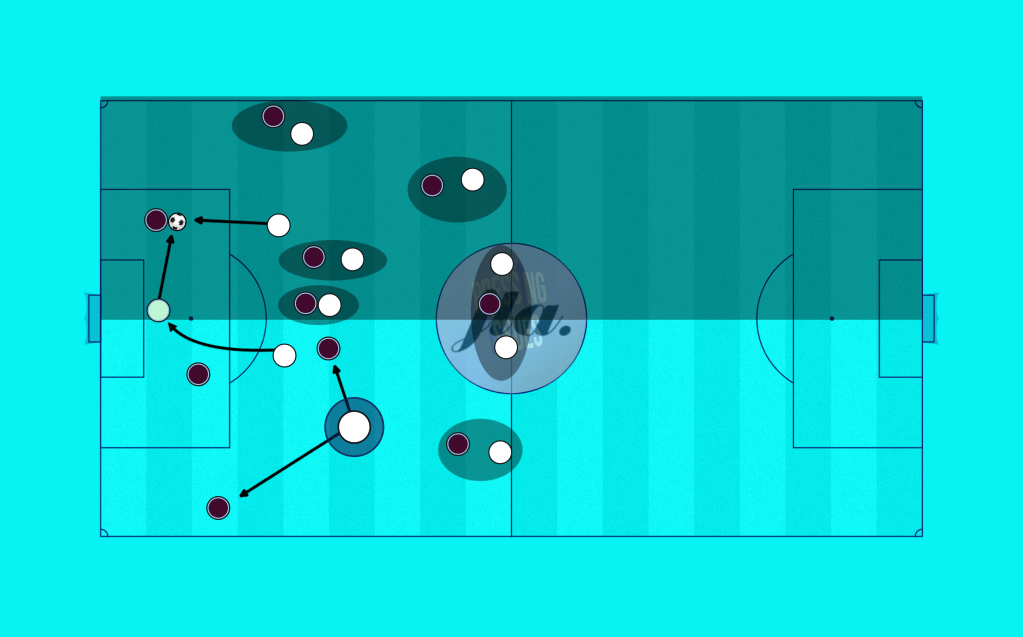

The danger of a hybrid press comes in these transitional moments, when the team is shifting from one side of the pitch to the other. As such, it is moments like these that teams might shift into a midblock and look to re-establish their high press phase from there.

But the high press phase itself holds the same weakness as a usual high press: the opponent always has a spare player. This is what Guardiola at City and Frank at Spurs try to combat with having their hybrid player switch between the two depending on the ball’s position. It leaves one of the opponent’s defenders free, but retains the shape to transition into a midblock as and when it’s required.

Then there’s Andoni Iraola’s Bournemouth, who, rather than embracing a weakness in the opponent’s backline, try to hide the weakness in their press by adding an extra layer of aggression. Guardiola went through a phase of trying this himself last season, but City were repeatedly caught out by it. Maybe it’s only a Bournemouth thing.

This leaves the non ball-side winger as the hybrid player again, this time responsible for jumping onto the spare midfielder, while being ready to shift across to the right-back. This system is considered ‘vertically-weakened’, owing to the hybrid player marking two players on different lines, while the other is ‘horizontally-weakened’ as the hybrid player tends to mark two players in the defensive line.

As mentioned, the aim of a hybrid press is to enjoy the benefits of protecting both space and possession, and by engaging in their high press phase in a solid structure. Because of this, there becomes an ease in switching from a high press phase into a more structured midblock. The ability of a team to transition from one phase of pressing to another is the fundamental importance when it comes to a successful hybrid press.

There we have it then. Four distinct styles of pressing, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses. The beauty of modern football is that no pressing system is the same, and it is always evolving. Who’s to say that in a few years’ time, we won’t have further, more complex variations of each system, as well as managers who are still trying to perfect the hybrid press to enjoy dominating every facet of OOP play.

Leave a comment